Type of Article: Presentation of a scientific concept and related research

Reading time: 7 minutes

Jessica Desamero, PhD

According to the CDC, cancer is the second leading cause of death in the US. Because of this, developing novel strategies for cancer treatment is of high interest. One method of cancer treatment would be to target cancer cells’ immortality.

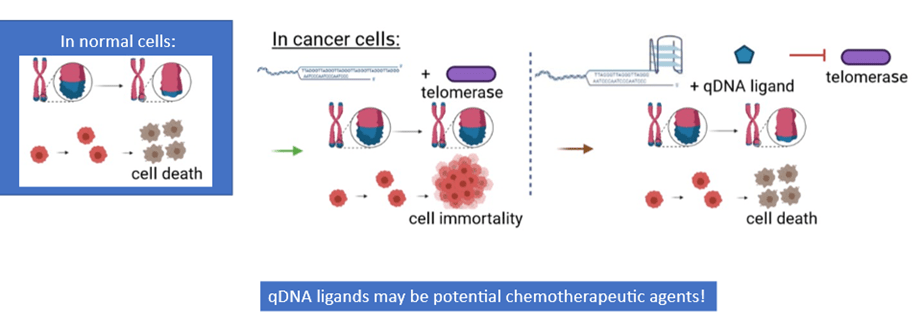

To elaborate, at the ends of a cell’s chromosomes are protective caps called telomeres. Normally, as the cell divides, these telomeres gradually shorten until they reach a critical length, which signals the cell to stop dividing, and eventually the cell dies. This is the normal life cycle of a cell, where they grow, then they age, then they die. But in cancer cells, an enzyme that is usually inactive becomes activated, and this enzyme is called telomerase. Telomerase helps keep the telomeres long, which would eliminate the cell’s stop signal. As a result, cells would divide indefinitely, rendering them immortal. These cells would then cluster together and form tumors, which are hallmarks of cancer. Now, if you can somehow stop telomerase activity, you can ultimately stop cancer from progressing. Enter telomeric G-quadruplexes!

The Structure and Role of Telomeric DNA G-Quadruplexes in Cancer

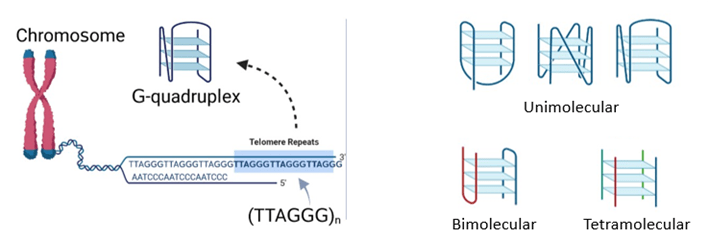

DNA G-quadruplexes (qDNA) are special secondary structures that can be formed from guanine-rich sequences. Telomeric G-quadruplexes can be found at the ends of telomeres, which, in humans, have repeats of the sequence TTAGGG. Multiple types of quadruplex structures are possible. These structures differ in the number of DNA strands, orientation of the strands and types of connecting loops present (Figure 1).

In cancer cells, when telomeric G-quadruplexes are formed, they block the telomerase enzyme from being able to interact with the DNA. Telomerase activity would halt, which allows telomeres to shorten again and restores the signal for cell death. This would then prevent further tumor growth and progression. Because of this anticancer effect, molecules that bind to and stabilize quadruplexes, or qDNA ligands, can serve as potential agents for cancer therapy (Figure 2).

Scientists have identified several qDNA ligands that can stabilize qDNA. However, not all molecules interact equally with quadruplexes. In addition, when evaluating the potential of qDNA ligands for use in chemotherapy, one crucial factor to consider is how they physically interact with quadruplexes. However, the structural details about how ligands and quadruplexes bind are still mainly unclear. And in cells, G-quadruplexes can constantly change in structure depending on the cellular environment; this may affect how they interact with qDNA ligands.

Our Research Purpose and Methodology

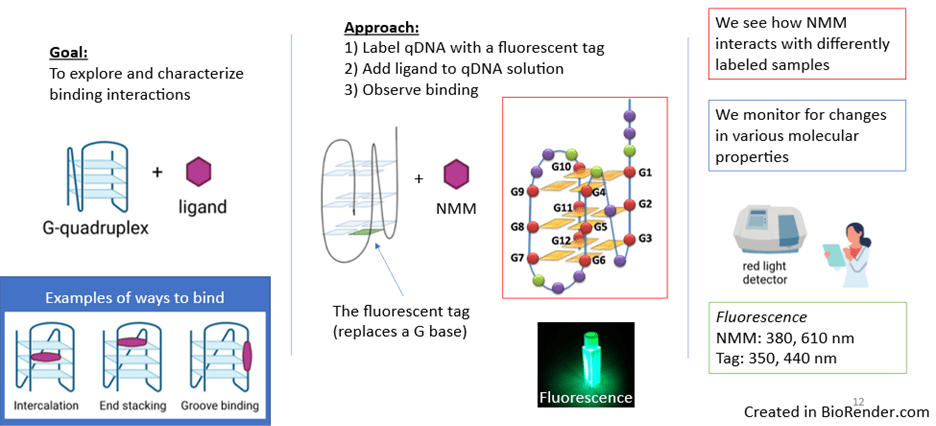

Our research goal was to characterize the binding interactions between G-quadruplexes and the qDNA ligand N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX (NMM). Our study involved putting qDNA and NMM together in solution and analyzing their molecular properties. One property we observed was fluorescence, or the ability of a substance to emit visible light after absorbing electromagnetic radiation. For analysis, we used advanced spectroscopy techniques that examine how matter interacts with light across different wavelengths and frequencies.

What is Generally Known and Unknown about How NMM Interacts with qDNA

Previous studies have shown that NMM has a moderate binding affinity for G-quadruplexes. Upon binding, the G-quadruplex switches from one structural form to another. In addition, NMM alone has weak fluorescence, but the presence of quadruplex enhances this ligand’s fluorescence. Moreover, we previously found that the extent of NMM fluorescence enhancement with quadruplex is much greater than with other secondary structures, such as DNA double helix. This shows that NMM highly prefers binding to quadruplex DNA.

However, two questions remain: how exactly does NMM bind to qDNA, and where exactly does it bind?

More on our Research Approach

To answer these questions, we worked with qDNA samples that were each labeled with a light-up, fluorescent tag. This tag resembles a guanine base in structure, and it replaces one of the guanine bases in the qDNA sequence. To be able to observe each section of the quadruplex individually, we used various qDNA sequences labeled at different guanine positions (G1-G12).

In short, we added NMM ligand to solutions containing the various qDNA samples. Then, with our various tools, we observed how NMM interacts with the differently labeled samples; we monitored the samples for changes in various molecular properties, including absorption and fluorescence. Both the tag and NMM are fluorescent, and the ranges to get the optimal fluorescence for these molecules are at different wavelengths. Therefore, we can evaluate ligand-quadruplex binding from two different perspectives (Figure 3). As a positive control, we used unlabeled qDNA.

Our Study Results

Probing qDNA Structure (circular dichroism spectroscopy)

First, we probed for changes in qDNA structure to see how the presence of NMM affects the differently labeled sequences. To do this, we observed how our qDNA samples differently absorb left and right circularly polarized light (circular dichroism) before and after adding NMM to solution. Here, a change in the shape of the spectra would indicate a change in secondary structure. Two scenarios happened:

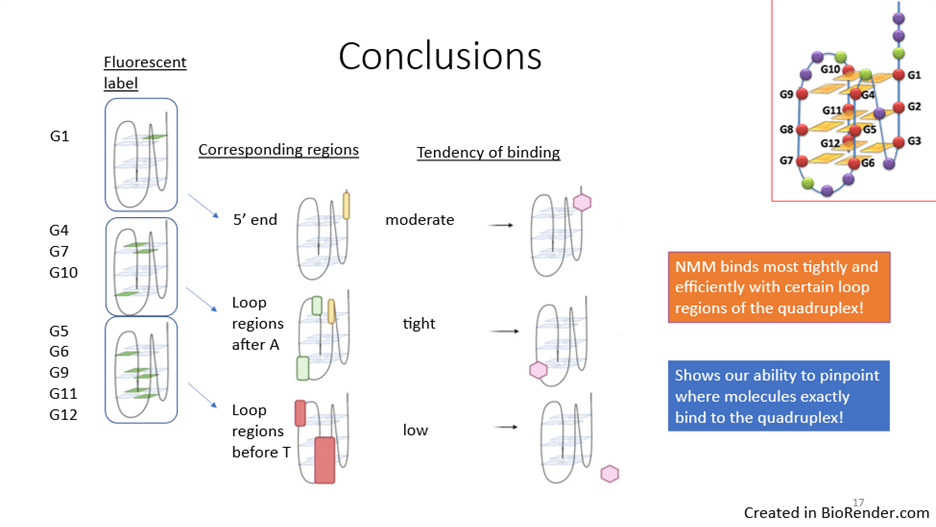

- G1, G4, G7, G10: The quadruplex switched from one structural form to another, as the spectral peak shifts from one wavelength to another. A similar scenario occurs with unlabeled qDNA, which may indicate binding.

- G5, G6, G9, G11, G12: no structural change occurred, as the shape of the spectra remained the same. This may indicate either a lack of binding or a lack of NMM influence.

After further analyzing the sequences where the switch occurs, we determined that G7- and G10-labeled qDNA had the greatest NMM binding strength. This suggests that NMM most likely binds to the positions on the quadruplex associated with G7 and G10.

Probing Fluorescence of NMM Ligand and of Tag on qDNA (fluorescence spectroscopy)

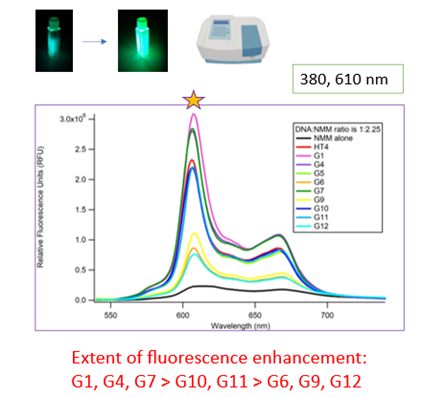

Second, we probed the fluorescence of NMM to compare how the different labeled samples affect NMM fluorescence. Here, the extent of fluorescence enhancement reflects the extent of binding. We found that NMM displayed the greatest fluorescence enhancement with G1-, G7- and G10-labeled sequences, as the spectral peak at 610 nm is highest with these qDNA samples (Figure 4, top).

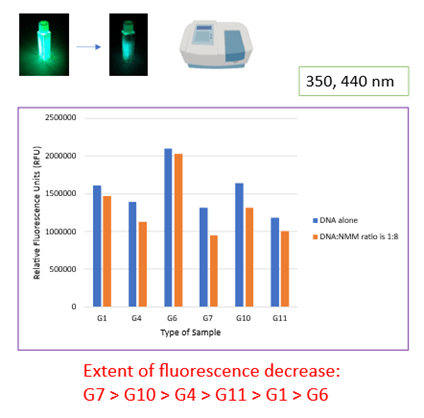

Third, we probed the fluorescence of the tag on the qDNA before and after NMM is added to solution. The tag alone is highly fluorescent, but this fluorescence decreases upon interaction with other molecules. This time, the magnitude of decrease in fluorescence intensity would reflect the extent of ligand-qDNA binding. We found that the fluorescence decrease is greatest with G7- and G10-labeled sequences, as the difference in fluorescence intensity before and after NMM is largest with these qDNA samples (Figure 4, bottom).

Both sets of fluorescence data suggest that the positions associated with G7 and G10 are the most probable binding sites. This correlates with our above data.

Conclusions

Our results combined suggest that the most probable NMM binding sites on the quadruplex are the locations associated with G7 and G10. G7 and G10 are associated with two loop regions, which suggests that NMM binds most tightly and efficiently with these loop regions, compared to other regions of the quadruplex. Our research also demonstrates our ability to pinpoint where molecules bind exactly to the quadruplex (Figure 5).

The information we obtained about quadruplex ligand binding could notably aid in the development of targeted drugs for cancer treatment. Additionally, various classes of quadruplex ligands have the potential ability to stabilize quadruplexes, but not all of them are fluorescent. Therefore, our model system of labeling qDNA with a fluorescent tag at different guanine positions can be used as a screening tool for these qDNA ligands.

This PhD research was done in the lab of Dr. Lesley Davenport at the City University of New York, Brooklyn College.

Figure Sources

Header Image: Created by author in Microsoft PowerPoint; using quadruplex image from Wikimedia Commons and cancer cells image from istockphoto.com

Figures 1-5: Created by author in Biorender

References

Desamero, J. (2023). Characterization of the Conformational Binding of N-methyl Mesoporphyrin IX with DNA Model Telomeric G-Quadruplex Forming Sequences. CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/5543/

Leave a comment