Target general audience: people who enjoy reading stories about scientists’ journeys, science lovers who also love anime

Reading time: 7 minutes

Jessica Desamero, PhD

Long ago, Samantha Cobos started on a journey to pursue a music and opera career. But after taking high school chemistry, she was amazed by her teacher’s ability to explain the subject. A spark of curiosity and passion ignited within her, and she felt a science career was truly meant to be.

Cobos had her first taste of hands-on science at Pace University, where she received a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. At Pace, the science department was small, but she learned and tried out what she could from every professor and their lab. “That’s what helped me really settle with myself that I liked science and that I was really curious about it,” Cobos said.

During the summer of 2016, Cobos dove deeper into science and participated in the Research in Science and Engineering (RiSE) program at Rutgers University, where she worked in the lab of Shishir Chundawat. One project explored the potential use of cellulose, the main structural component of plant cell walls, as renewable energy. This internship solidified her interest in research. “The thing that really, really inspired me there was seeing all of the equipment and the space and the joy that people had working in a space like that,” Cobos said.

Her ten billion percent excitement for chemistry continued throughout college in other ways. Cobos became the secretary of the American Chemical Society (ACS) club chapter at Pace and won the ACS Scholar Award as a junior. She also served as a teaching assistant for general chemistry and organic chemistry classes for three years. From these activities, she found that being a leader and teacher of science was exhilarating. Her combined love of research and teaching led her to pursue graduate school.

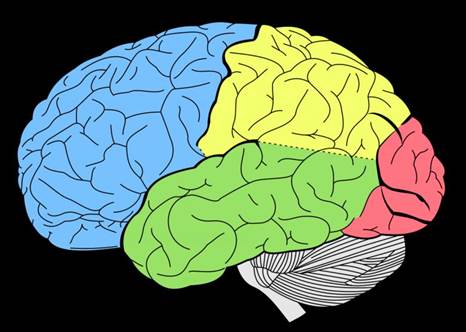

Studying The Chemistry Behind Brain Disorders

Cobos received her PhD in Chemistry from the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center. She worked at CUNY Brooklyn College in the lab of Dr. Mariana Torrente, whose lab worked on studying neurodegenerative diseases, or conditions where parts of the nervous system, especially the brain, gradually die. Cobos specifically studied prion proteins, which are proteins that can trigger normal proteins to fold abnormally, or misfold.

“When a prion protein (PRP) turns ‘on’ into the prion state where it misfolds and loses its original function, it can’t change back, and unfortunately this leads to a lot of catastrophic side effects within the cells, specifically in the neurons of humans,” Cobos said.

In animals, misfolded prions can cause fatal diseases that harm the brain, such as mad cow disease and scrapie. In both conditions, prions cause motor neurons to die, which in turn leads to holes in the brain tissue and eventually death of the organism. This disease can spread to humans upon consuming the diseased tissue. So far, there is no cure for prion diseases.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast, also known as baker’s yeast, also have prion proteins that lose their original function when they misfold. The key difference is that, unlike in humans, misfolded prions can switch back and forth into their original form and function, as well as a new prion function. This allows them to adapt to changing environments. Cobos studied how this switch occurs.

“The thought behind my PhD project was if we can understand how this switch happens and the elements that control this switch, can we then apply that to prion and prion-like proteins in humans to then understand disease and hopefully find a cure?” she said.

Cobos published several first-author research papers and presented her work at several research conferences.

In addition to research, Cobos taught general chemistry courses at Brooklyn College, an underrepresented minority (URM) serving institution. Her love for teaching continued to grow, and she particularly valued teaching students that looked like her. “It was fulfilling knowing that I could connect with students on that level, and the progression of their grades through the semester showed that the students were truly learning.” Cobos said.

From Yeast to Fruit Flies

Currently, Cobos is an NIH IRACDA postdoctoral fellow at Stony Brook University in New York. She works in the lab of Joshua Dubnau, whose lab studies the modes of action behind two neurodegenerative diseases, one of which is called Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) (think: the ALS ice bucket challenge). Here, Cobos continues to study neurodegenerative diseases and protein misfolding, but on a much broader level.

And instead of yeast, she now works with fruit flies. She finds them cool to work with, and she loves how working with flies allows her to ask a wide range of broader questions. “They are the smallest organism that you can work with that still has a brain, which helps a lot when you’re trying to study something like neurodegenerative disease,” Cobos said.

Using flies, which can live for up to 80 days, also allows Cobos and her lab to study the effects of aging. For instance, they can observe if misfolding spreads in aged flies. They can also induce misfolding in younger flies, observe what occurs, and possibly relate it to what would happen in a younger patient. “It really gives us a huge variety of tools to just play around with everything,” Cobos said.

“Hopefully we can get a bigger clue as to what the ramifications are of neurodegenerative diseases and see if we can get some hint as to how to stop it earlier.”

A Future in Teaching + Hopes for a Science Media Literacy Course

Cobos enjoyed serving as a teaching assistant at Pace and an adjunct instructor at Brooklyn College. And after teaching laboratory and lecture classes as part of her IRACDA postdoc program, she fell even more in love with the practice. She particularly takes delight in her interactions with students.

“I love seeing that light bulb moment in a student when an idea finally clicks in their minds. That’s one of my favorite things,” Cobos said. “It’s really fun just seeing that moment where it starts to make sense, and it’s even better when they get curious and start asking their own questions. I don’t get tired of it.”

In the future, she hopes to become a principal investigator and help students fuel their curiosity. “The exciting part about science is that there really are no stupid questions. Everything is an angle that you should be considering. It really gives people the space to play, and I want to help facilitate that for students.”

Apart from teaching chemistry and neuroscience, Cobos also wishes to create her own science media literacy course. For this course, she envisions analyzing the authenticity of the scientific content behind current science-related media.

“As an anime fan, I have students that come up to me and be like, have you watched “Dr. Stone”? Have you watched “Cells at Work”? I’m like, yes, I have. They’re really fun. They’re really cute. But they start asking about the actual scientific content of it and whether or not they can use it as studying material. Getting this question so much with regards to different types of media has gotten me thinking, what is the validity of these things?,” Cobos said.

In this course, Cobos would evaluate what shows do right in terms of portraying science correctly, and what they do not do so well. She would also get into whether watchers can trust what they see on TV and apply what they learn from these media onto real life.

Cobos finds this course particularly important in these current times of distrust in the sciences. “A course like this, even geared towards non-scientists especially, would help give a little bit of a feeling of healthy skepticism that doesn’t completely distrust science 100%,” she said. “I’m hoping to create courses like that in the future to help people gain more of a trust for the scientific process.”

Dr. Samantha Cobos was interviewed for this article.

Header Image Source: Created with Canva. The headshot was provided by the interviewee.

Other Image Sources:

Figure 1 was created by author with Canva, using images of “Dr. Stone” and “Cells at Work” art found via Google search.

Leave a comment